So you're in your new role. What do you actually do in the first month?

You know what you need to be thinking about. But what actions should you take?

Here's some pragmatic and functional things you can put into play, stuff that will help you understand the task ahead and how you can take it on.

So, your first month, real world. What do you actually do?

Here's a set of hands-on suggestions for specific activities to cover that should point you in the right direction.

Needs and objectives #

In these first 30 days you need to understand the objectives that will drive you from two directions:

- the goals of the business

as it moves forward in its mission - the needs of the delivery team

as they fulfil client projects

Consequently, your activities should look in both these directions.

The business objectives #

There's several things you can do here:

1. Dialogue with the CEO #

Naturally, you will be meeting with the CEO at the beginning of your time, and again at the end of the first month to summarise your analysis and insights (and maybe once or twice in between, too).

The agenda of your first meeting, or a follow-up if necessary, should include an in-depth discussion about the mission and goals of the business, and how it's seeking to achieve those. That should cover:

- The vision and mission

- Not just the trite or top-line view

- The motives that drive the vision

- The aims of the mission

- The strategy for achieving those aims

- What is the current quarterly/half-year objective?

- How is it being implemented?

- How is it being measured?

- And what is the next objective?

- The business should have a goal-setting or objective framework of some kind in place

- E.g. OKRs, Big Rocks, VMOS(T/A), or some other form of KPIs

- What is the 1 year, 3 year, 5 year, plan?

- What is the current quarterly/half-year objective?

- How role does client delivery play in fulfilling these?

- How does the CEO perceive the place of customer and project outcomes in the life and future of the business?

You should have a full discussion with the CEO on the mission and goals of the business, and how it's working to achieve those.

Follow your discussion with the CEO with any reading you can — documents and documentation on the objectives (current and past) and their outcomes, including slide decks, board reports, memos, and more. It's important to understand how this stuff is summarised, and how it's communicated to the wider organisation.

2. Discussion with the exec and heads of departments #

It may not be appropriate in your first meeting with the new exec team, but it's important to understand the same questions at this level. So add an agenda point for one of your first few meetings to cover this as part of 'bringing you up-to-speed'.

However, your focus when you're asking these questions goes beyond just re-hashing the same material and adding colour. What you're really listening for when asking these questions at this level is:

- How do the exec team members (CTO, COO, CMO, CISO, etc.) and their business units own these things?

- the vision, the mission, the strategy, especially the quarterly/half-yearly goals and longer-term plan

- How do the exec team and their business units interpret these things and turn them into action?

- how do the objectives cascade down into actionable goals in each part of the organisation?

- what are they putting into practice to achieve those objectives/outcomes?

- are they measuring things?

- and if so, what?

How do the objectives cascade down into actionable goals in each part of the organisation?

You should probably consider doing the same with heads of departments and others significant people who aren't part of the exec team.

The delivery unit's needs #

As well as the objectives of the business, you need to understand how the customer/project delivery unit works as a whole, how individual teams work within it, what needs they have and what challenges they face.

Some of this will come from observation and one-to-one discussions, but some may need a more structured approach.

3. Workshops with the delivery team #

Whilst ad hoc or impromptu conversations with delivery personnel are important, as we said previously, you may also consider running a workshop or two to help you understand how things work in this new organisation.

Here's a couple of suggestions. You may have other thoughts yourself.

3.1. Hold a project post-mortem #

Take a recent client project and conduct a retrospective or post-mortem together. Doesn't need to be one that's been problematic or failed — in fact, assessing a successful one is probably more politically astute.

You should run this using a Retrospective meeting format (i.e. what went well?; what didn't go well?; what could be improved or tried?; what did we learn?).

You probably ought to send a questionnaire in advance, for those who like some unpressured thinking time, with variations on these questions (e.g. use the 4 Ls — 2/3 things you liked, lacked, longed for, learned).

You should definitely capture the outcomes and send a summary or recap to everyone.

3.2 Write the CEOs speech #

Take ideas for a new product or service for the business based on recent learning or a specific project outcome. Choose one.

Imagine that it's going to be launched in 12/18 months following an extended effort by the delivery team. The CEO will give a speech at an industry conference to announce it.

Split into 2/3 teams and write the CEOs speech. Each team presents it to the wider group.

Paying attention #

As well as the specific outcomes, you're really listening for the undercurrents in these workshops.

- How do these people work together?

- How do they feel about the work they do?

- How do they feel about the business as a whole and their contribution to it's goals?

- What are their gripes and frustrations?

- Are there obvious challenges or difficulties?

The things you detect will start to form the basis of the strategy you'll need to be putting in place.

Stakeholder mapping #

A really useful exercise to understand the organisation and who's concerned with what you is to create a stakeholder map. You may be familiar with this sort of thing already, so if so here's a refresher.

Factors to consider #

What you're trying to examine with this sort of task is how the organisation will respond to what you do in your work.

- Who has the most influence on your freedom of movement?

- Or, whose say-so will determine what you can and can't do?

- Which people will be most affected by changes you make?

- Or, if and when you change things, whose day-to-day will change (for better or worse)?

- Who controls the resources?

- That's all the resources — finances, people, technology, time, and so on.

- How should you handle important people who actually won’t be considered stakeholders?

- Some people will think of themselves as stakeholders but, in fact, only need to be informed of changes.

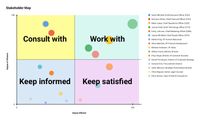

There's many ways that you can do that but the outcome might look something like this chart below.

This is only example data, of course, all completely made up, and likely missing a good number of job roles out, too. That said, this is an illustration of how the exercise can help build your conception of the organisation, and how it can shape how to approach your role and impact.

If you're trying to work out how to score individuals in the organisation, remember that you're trying to determine the top motivations and interests of your stakeholders. When deciding the driving force of stakeholders, consider:

- Who has a financial stake/interest.

- Who has an emotional interest (don’t underestimate this; if this project was someone’s “baby,” keeping them happy and in the loop is critical).

- What are the top motivations for each stakeholder?

- Who are the biggest supporters?

- Who are the biggest non-supporters or naysayers?

What are the motivations and interests of your stakeholders?

How will the organisation respond to what you do?

The map you produce #

The idea with this chart is to end up with 4 quadrants.

- Work with

- or Involve in shorthand

- Those you'll work with most directly in developing and executing your strategy. These are also people with skin in the game, who will influence what you do and be affected by the choices you make.

- Consult with

- or Consult

- Those whose views are important and probably have a fair bit of authority, but won't be so affected by directly by changes you make, and certainly not in their daily work.

- Keep satisfied

- or Approval

- People who will be affected and probably need to adapt how they work — so don't frustrate them! — but they'll be responsive rather than active agents in your changes.

- Or, people who may have some governance or other control over how you execute your work, such as HR, legal or finance, say.

- Keep informed

- or Inform

- These are probably not actual stakeholders, but will nonetheless take a keen interest in what you do.

- Some may be marginal cases, but it's good to be hard-nosed in assigning people to this grouping — over-consulting will kill your progress.

Note: there are other approaches to charting things that could work, such as the Three I-s method — influence; interest; impact. Do whatever's most appropriate for your context.

Data for the above came from a simple spreadsheet looking like this.

You can check out the stakeholder map spreadsheet for yourself.

When you have your map #

It's important to be as empirical as possible, so make sure you validate what you've produced.

- Check it over with key people and review each person's position on the chart.

- Change as needed, making a record of the reasoning if that's helpful.

Once you have your map finalised, this is the basis of an engagement plan — both now, in this first 30 days, and ongoing as you and your strategy get more embedded. So, review it regularly, and update it throughout your tenure.

Assess the risks #

We'll talk in more detail elsewhere (page forthcoming) about better approaches to managing risks. However you go about it, the point here is that risk assessment is a helpful practice for getting yourself oriented when you first start in your new role as a director of project or service delivery.

The point of an assessment of risks at this stage is layered:

- to understand the forces, internal and external, that you're may confront

- the likelihood of them having affecting the delivery unit in the business

- the scale of the impact they might have

- whether they can be mitigated

- and if so, how

- and how that will your ability to design and successfully execute your strategy

The outcome of your assessment will shape the plans that you put in place.

An assessment of risks is a helpful practice to get oriented when you start a new delivery leadership role.

Altitudes of thinking #

What's worth stressing here is that that you should be approaching this by thinking of risks at different altitudes.

- Global

- National

- Organisation

- Service

- Team

By separating out the altitudes of risk in this manner you can adjust the way you think about them. Risks at different altitudes impact in different ways, and therefore demand that we respond differently.

Global and national levels #

Political, social, societal and technological factors all operate at this level.

👉Most are fairly slow-moving, appear with plenty of warning (election cycles, say) and any risk posed can be easier to mitigate as a result (though some are very uncertain, such as the political and economic impacts of Brexit, the US tariff regime, etc.).

👉Others may seem unlikely but can appear quickly with devastating effects. As we've seen in recent years with the Covid-19 pandemic, there are risks that operate at a global level that have clear and direct impacts at personal level.

👉Some (war, say) are exceedingly rare, in the main, and probably don't need to feature on your register.

The risks are real, though our response is less about removing the risk and rather the actions we might need to take.

On the risk of pandemic, note also that global disease is no less likely now than it was in 2020, and global attitudes to healthcare responses, vaccines in particular, are shifting under continuing pressure from adherents to conspiracy theories.

It's worth remembering also that there's some risks operating at the Global and National level that don't separate neatly between the two — societal and market fluctuations or full-on shocks are often both, for instance.

Organisational level #

At this level we're considering the risks that face the organisation. In general, you should be considering things in these areas:

- strategic risks — what will impact how the business can achieve its goals, and long-term health?

- e.g. shifts in technology or market; competition; strategic capabilities; etc.

- operational risks — what issues with processes, people, or systems may impede operations?

- e.g. scalability of key IT/software; key talent retention; data vulnerabilities; unscaling workflows; supply chain dependencies; etc.

- financial risks — what will affect the financial stability and longevity of the business?

- e.g. runway; access to funding; loan liabilities; market or economic volatility, including inflationary pressures; taxation changes; etc.

- compliance risks — meeting regulatory, legal, or industry standards

- e.g. changes in regulatory climate, such as with Brexit; data management regulation; changes to tax or employment law; etc.

Many of these dimensions may feature in business-as-usual, the things the organisation naturally faces and remediates in the course of business.

But it's vital to take a good, hard look at organisational risks — clear and specific issues must be identified wherever possible.

You do not want to get caught out by Donald Rumsfeld's ‘unknown unknowns’ through a lack of thoroughness or due diligence.

Service (or product) level #

Here of course we're concerned with risks to the service or services being offered or run by the business.

The risks here will vary according to sector, industry, specialism, and so on. That said, there are common perspectives to understand and interpret the risks regardless of the specific context.

Take a walk-through

You'll obviously have some demonstrations anyway, to understand what the business does and how it does it. But do that with a risk hat on, aiming to spot and discuss potential hazards.Consult the specialists

Team members have the most experience about delivering the products and services, and therefore the greatest understanding of what can go wrong, how, when, and what can be done about it.Review incidents

Assess past outages or other deterioration events — there may be obvious issues or repeating patterns. What was done to fix things, how much effort did it take, and what changes where made as a result?Given this is just your first 30 days, you'll need to prioritise this for recent and/or large incidents.

Consider scale, severity, scope, and nature

- Who could be harmed (i.e. staff, business, customers, general public, etc.)?

- and by a loss or degradation of what parts of the service or product?

- What is the actual harm they might experience (i.e. financial, physical, reputation, etc.)?

- Who could be harmed (i.e. staff, business, customers, general public, etc.)?

Understand commitments

What has the business committed to doing for customers or clients, or for end-users? What are the contractual obligations, and the penalties or forfeits incurred?

What you're trying to achieve here is to understand both what's important and what's vulnerable in how the business operates and what it offers to its customers. Your job is to ensure safety and security in the services you deliver and products you offer, so you must know what you have to guard and where you'll need to build resilience or strength.

Team level #

And then finally, you're assessment of risk should review the delivery team.

At the team level you're looking at a number of things.

- Technology, particularly

- tools, platforms, and ecosystems used

- performance and reliability

- their fitness for usage

- their robustness and broad applicability

- testing, automation, quality engineering

- security practices

- attitude to new technologies and adoption

- skills coverage

- future-proofing

- People, particularly

- personnel, skills and capabilities

- team formation and structures

- team dynamics and interactions

- team practices and behaviours

- team roles, responsibilities, and leadership

- team robustness and resilience

- training, learning, knowledge-sharing

- capacity

- future needs

- Processes, particularly

- project management methodologies and adherence

- project ceremonies

- project roles and responsibilities

- security procedures and protocols

- data management practices

- quality assurance

- Knowledge, particularly

- documentation, for projects and processes

- knowledge-sharing

- learning and development practices and processes

- Clients, particularly

- responding to change

- building plans

- demanding or problematic client relationships

- stakeholder management issues

- governance practices and quality

From a risk assessment perspective, here you're aiming to get a clear view of how likely things are to go wrong within the team, where are the weak points that are likely to give way, and if they do buckle then how resilient are the team.

We've covered a lot of dimensions here, but this is not meant to be proscriptive — you don't need to do all of this stuff in a risk assessment at this early stage, and in the limits of your first 30 days you certainly won't be able to.

Rather, laying it all out here is about putting things into your mind to consider as you get your feet under the table. Some things will chime with you as you go walk-about in your new role, a nudge to take to consider the things that may merit a closer look.

We'll take a look in a later section of The Handbook at some alternative and usefully practical ways of actually looking at risks, knowing what's important to keep an eye on, and then actually keeping track.